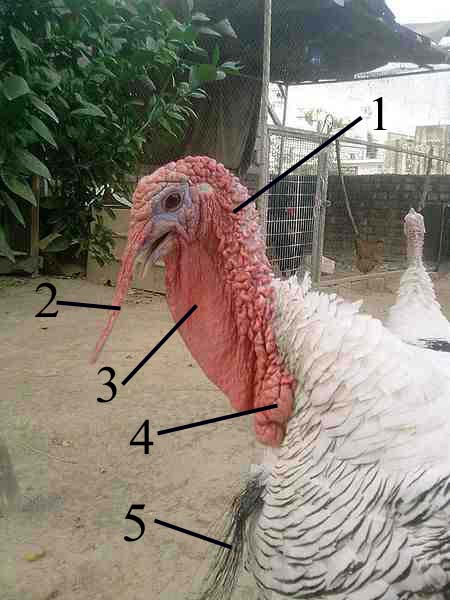

Turkey

They are among the largest birds in their ranges. As with many large ground-feeding birds (order Galliformes), the male is bigger and much more colorful than the female. The earliest turkeys evolved in North America over 20 million years ago. They share a recent common ancestor with grouse, pheasants, and other fowl. The wild turkey species is the ancestor of the domestic turkey, which was domesticated approximately 2,000 years ago by indigenous peoples. The type species of the wild turkey is (Meleagris gallopavo). Turkeys are classed in the family Phasianidae (pheasants, partridges, francolins, junglefowl, grouse, and relatives thereof) in the taxonomic order Galliformes. They are close relatives of the grouse and are classified alongside them in the tribe Tetraonini.

Wild turkeys feed on various wildlife depending on the season. In the warmer months of spring and summer, their diet consists mainly of grains such as wheat, corn, and of smaller animals such as grasshoppers, spiders, worms, and lizards. In the colder months of fall and winter, wild turkeys consume smaller fruits and nuts such as grapes, blueberries, acorns, and walnuts. To find this food, they have to continuously forage and feed most during the sunrise and sunset hours. Domesticated turkeys consume a commercially produced feed formulated to increase the size of the turkeys. To supplement their nutrition, farmers will also feed them grains wild turkeys eat such as corn.

Turkeys participate in a number of grooming behaviors including: dusting, sunning, and feather preening. In dusting, turkeys get low on their stomach or side and flap their wings, coating themselves with dirt. This action serves to remove debris build-up on the feathers and also clog tiny pores that parasites such as lice can inhabit. Sunning for turkeys involves bathing in the sunlight, for their top and bottom halves. This can serve to liquidate the oil that turkeys naturally produce, spreading over their feathers and dry their feathers from precipitation at the same time. In feather preening, turkeys are able to remove dirt and bacteria, while also ensuring that non-durable feathers are removed.

Though domestic turkeys are considered flightless, wild turkeys can and do fly for short distances. Turkeys are best adapted for walking and foraging; they do not fly as a normal means of travel. When faced with a perceived danger, wild turkeys can fly up to a quarter mile. Turkeys may also make short flights to assist roosting in a tree.

Natural Breeding:

Courtship: Toms (male turkeys) engage in courtship behaviors like gobbling, strutting, and displaying their feathers to attract hens (female turkeys).

Mating: Once a hen is receptive, she will crouch, signaling the tom to mate.

Mating Ratio: A ratio of 1 tom to 6-8 hens is generally recommended for natural breeding, according to the Poultry Site.

Nesting: Hens will build nests in a safe, secluded area, laying 9-13 eggs in a clutch.

Incubation: Hens will incubate the eggs for approximately 28 days.

Breeding Season:

Timing: Breeding typically occurs in the spring, with hens laying eggs in late winter or early spring.

Factors: The length of daylight and temperature play a role in stimulating turkey breeding.

Incubation:

Incubators: Turkey eggs can be incubated in a controlled environment using incubators to maintain the correct temperature and humidity.

Piping: At about 25 days, turkey eggs will start to “pip” (chicks tapping at the inside of the shell), and eggs should be moved to a hatcher.

Hatching: Once the eggs hatch, the poults (baby turkeys) need to be kept warm and dry.

Raising Poults:

Brooding: Newly hatched poults need to be brooded in a warm, dry environment with access to food and water.

Housing: Turkeys need secure housing, with access to pasture or a run, and roosting poles.

Space: Provide adequate space for turkeys, with 10 sq ft per bird in a shelter and 20-30 sq yds of pasture per bird.

Health and Management:

Selection: Choose healthy and strong turkeys for breeding.

Nutrition: Provide a balanced diet for both breeding and growing turkeys.

Disease Prevention: Implement biosecurity measures to prevent disease outbreaks. Turkey poults are very susceptible to bacteria that other poultry carry. Poults should therefore be raised only with other turkeys.

Heritage Turkeys:

Natural Breeding: Heritage turkeys can breed naturally and most will brood their eggs and raise them.

Nesting Boxes: Offer nesting boxes at ground level for hens to lay and brood eggs.

Separation: During the breeding season, it’s crucial to separate the toms to prevent fighting and potential injuries to the hens.

We hope to be able to offer turkeys for sale as well as eggs for hatching in the near future. NWF seeks to have as many of the heritage breeds as possible and will continue to expand with this goal in mind.

Turkeys at Natural Ways Farm (NWF)

After a distressing experience in 2023 when bobcats killed our turkeys, we decided to start over in 2025. We currently have a Royal Palm Tom (male), and a Blue State hen (female) and hope to have poults soon as the hen is mature and mating. Both varieties are heritage breeds and are on the watch list since their numbers are limited. NWF seeks to preserve heritage breeds whicle appreciating their unique contribution to nature.

The Slate, or Blue Slate

The Royal Palm